By Dennis Sadowski

The city of Oberlin had its origins in the minds of two ministers who envisioned an intentional religious community focused on simple living and following God’s commandments to realize “the Christian conversion of humankind.”

The Rev. John J. Shipherd and fellow missionary Philo P. Stewart made plans in 1832 to find land west of Elyria, where they were living with their families. They settled on a location 9 miles away in heavily forested Russia Township, a tough place to farm but idyllic, they thought, for their commune.

Gary J. Kornblith and Carol Lasser, retired Oberlin College history professors, tell the story of the town’s origins in their 2018 book “Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, Ohio.”

The book is a deeply researched and fascinating review of the town’s history from its founding in 1833 through the early 20th century. It captures the enthusiasm and motivation of Shipherd, Stewart and their followers as they established the community and opened a school, the Oberlin Institute, now Oberlin College.

The ministers’ desire to start a faith-based community emerged during the second Great Awakening, a Protestant rebirth during the late 18th and early 19th centuries that sparked antebellum reform movements. They were especially inspired by the writing and celebrated ministry of the Rev. John Frederic Oberlin in rural Alsace, France.

“The motivation for Oberlin is to catch the wave, if you will. They are woke,” Kornblith said of Shipherd and Stewart.

“They were home missionaries. This is evangelicalism, which has a different connotation now, but this is an evangelical network spreading the word, the good news,” he said.

Shipherd envisioned a school that would enroll men and women regardless of age. The plan was to develop “gospel ministers and pious school teachers,” Shipherd wrote in the prospectus describing the plan. Within a few years discussions emerged to open enrollment to Black Americans, placing the institute, and by extension the community, in the forefront of the abolitionist movement and the promotion of equality among all people.

Kornblith and Lasser trace the history of the town as it followed an anti-slavery path through the Civil War years, a temperance campaign after the war and the emergence of stereotyped portrayals and gradual widening of discrimination that Blacks faced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Shipherd, his wife Esther and their children moved from Elyria in September 1833, about three years after they arrived in Ohio. He had served in ministry in Shelburne, Vermont, beginning in 1827. There, he felt “the finger of Providence points westward.”

An upstate New York native, Shipherd was born in 1802 in what the authors describe as a “well-to-do, politically prominent, white, slaveholding family.” Despite his family’s social status, he desired early on to become a preacher and set out at 25 to do so.

The Shipherd family arrived by steamboat in Cleveland on Oct. 7, 1830. Within a week he became a minister at the First Presbyterian Church in Elyria, then a village of 700. He lost the job less than a year later as some congregants objected to his calls to embrace temperance.

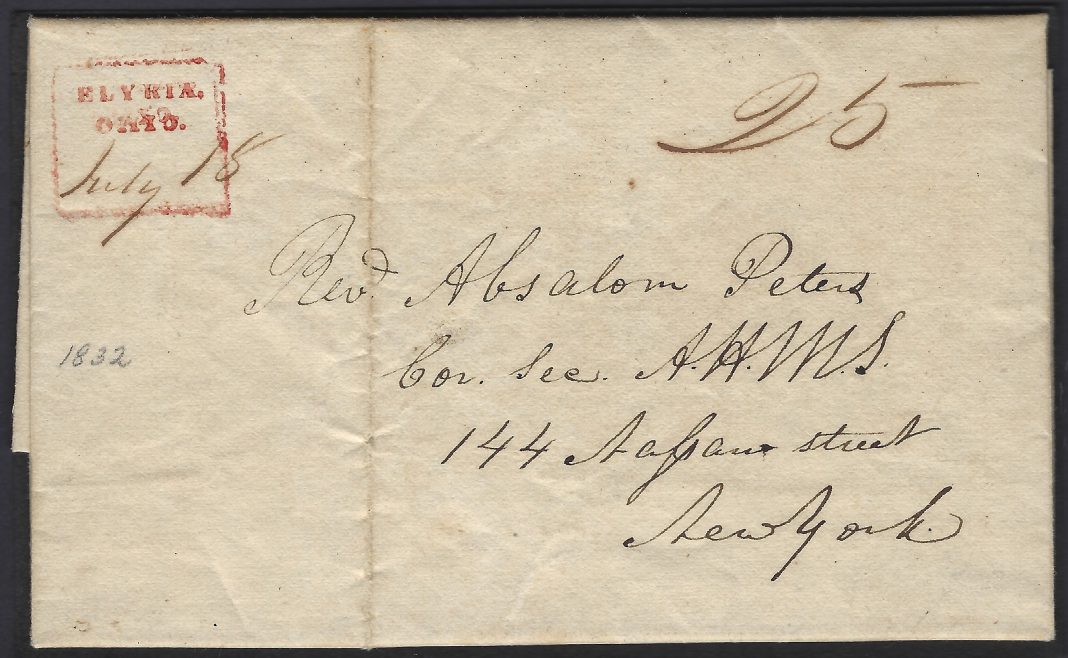

The front of a stampless letter written July 5, 1832, by the Rev. John J. Shipherd, co-founder of Oberlin College, is shown. Sent to a home mission official in New York City, it has a boxed Elyria postmark with a manuscript date of July 18 and “25” that indicates the postage rate for a letter traveling more than 400 miles.

Meanwhile, Stewart and his family moved to Elyria in 1832 to prepare for ordination under Shipherd. He had been a missionary to Choctaw Indians in Mississippi. Together they formed a plan that led to Oberlin.

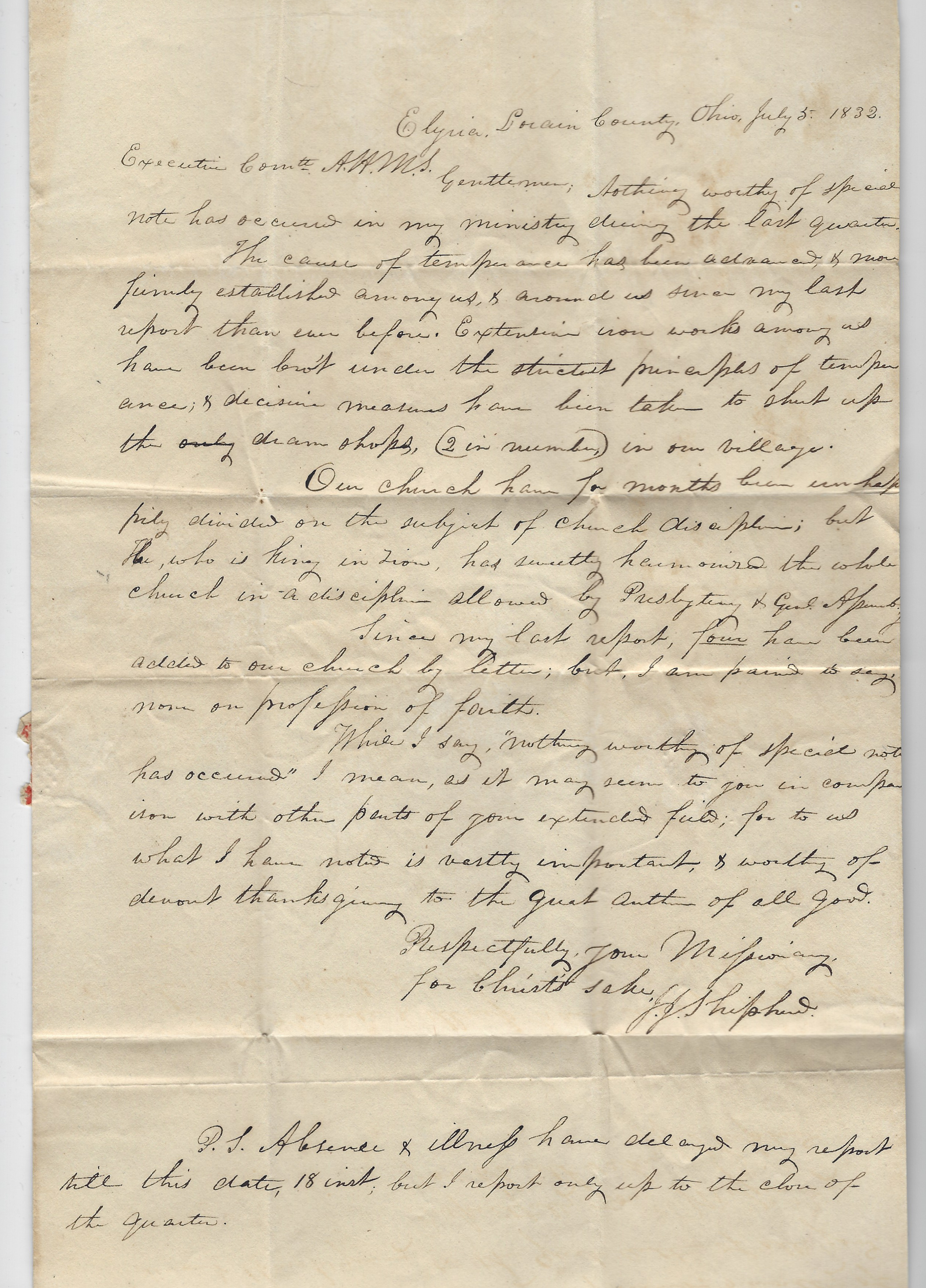

Along the way, Shipherd had been sending reports about his ministry to the Rev. Absalom Peters, corresponding secretary of the American Home Missionary Society in New York.

One such report survives and is in an Elyria postal history exhibit developed by Dave Wessely, owner of A-One Covers.

The one-page letter, mailed without a stamp, is dated July 5, 1832, weeks before Shipherd lost his church position. It is postmarked with a boxed Elyria cancellation with a manuscript date of “July 18.” The number “25” is written in the upper right corner indicating the postage rate at the time for a letter traveling more than 400 miles.

The type of cancellation was the first used under Heman Ely, Elyria’s founder and first postmaster. It was used from 1829 to 1833.

In his correspondence, Shipherd opened by writing: “Nothing worthy of special note has occurred in my ministry in the last quarter.” He described his efforts to teach discipline in Christian principles and “the cause of temperance has been advanced & now firmly established among us.” He indicated that the church had four new members “by letter, but I am pained to say none on profession of faith.”

Perhaps having second thoughts, Shipherd decided to clarify what he reported in his opening, penning that he meant “in comparison with other parts of your extended field; for to us what I have noted is vastly important and worthy of devout thanksgiving to the great author of all good.”

Surviving letters such as Shipherd’s offer a glimpse of life in Elyria nearly two centuries ago. That it was written by an individual of historical significance makes it all the more meaningful when studying history.

Club Meeting

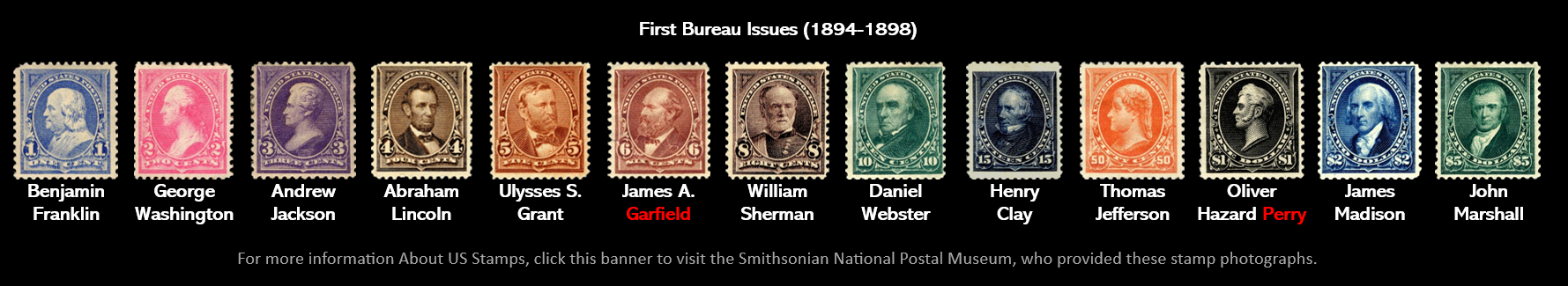

Ray Beer, a member of the Garfield-Perry Stamp Club, will discuss the proliferation of modern-day counterfeit stamps at the next meeting of the Black River Stamp Club on April 16. Doors open at 5 p.m. at the Lorain Public Library’s North Ridgeville Branch, 35700 Bainbridge Road.

Dennis Sadowski can be reached at sadowski.dennis@gmail.com.