By Dennis Sadowski

Those five- and nine-digit numbers in our mailing addresses seem to be a normal part of life that hardly gets noticed.

Known as a ZIP (zone improvement plan) code, the digits can be found on virtually every piece of mail across the country.

But more than 60 years ago there were no routing numbers on the vast majority of mail. It took a massive marketing campaign to help the public learn what those mailing codes were meant to do.

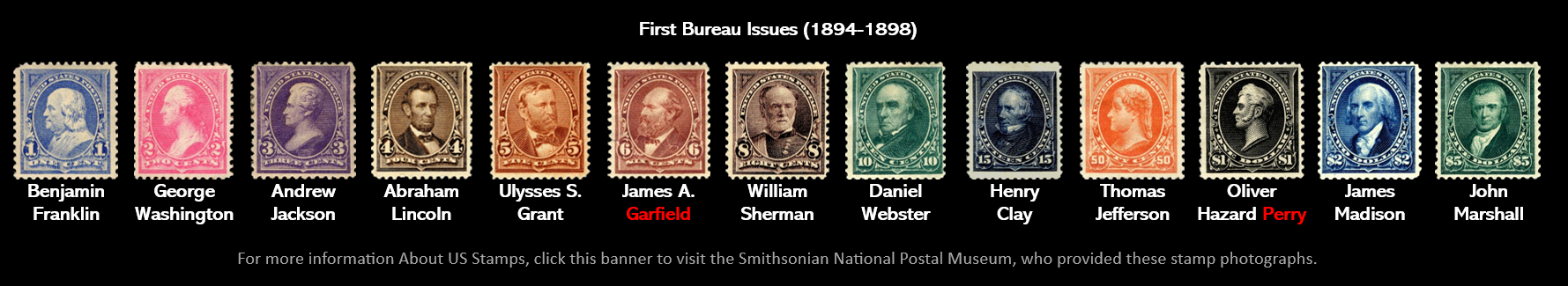

Launched July 1, 1963, the post office formalized a postal zoning system that assigned numbers to communities and neighborhoods based on geographic regions, according to the Smithsonian National Postal Museum website. It built upon the Postal Delivery Zone System that was implemented in 1943 primarily in large cities such as Cleveland to aid in mail sorting and delivery.

Postal officials developed the ZIP code as mail volume doubled from 33 billion pieces in 1943 to 66.5 billion pieces in 1962, spurred by growth in advertisements and periodicals. Mail handling was not mechanized then and local post offices were struggling to keep up with more material to deliver.

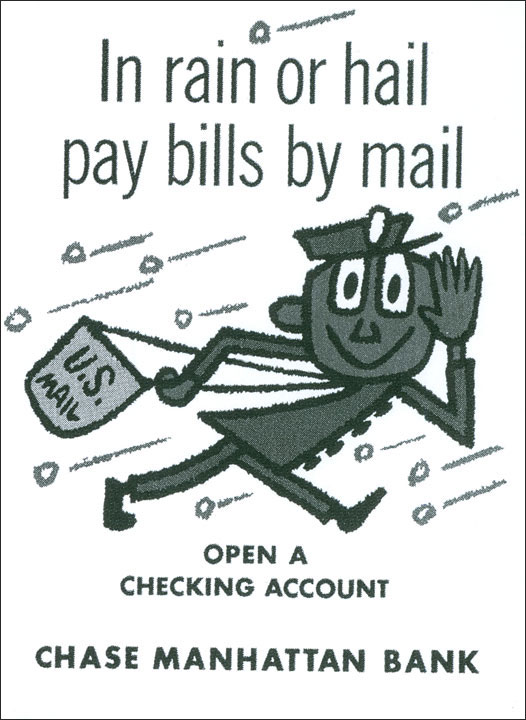

To help acquaint postal customers to the new concept, the former Post Office Department developed a nationwide marketing and educational campaign. It featured “Mr. Zip,” a caricature of a smiling mail carrier with a mail bag slung over one shoulder.

Mr. Zip, however, was not a post office innovation. He was created for Chase Manhattan Bank’s 1950s bank-by-mail campaign by the ad agency Cunningham and Walsh. The American Telephone and Telegraph Co. later acquired the image and offered its use to the POD at no cost.

He first was known as the not-so-catchy “Mr. P.O. Zone.” Officials smartly renamed him.

While some postal employees viewed Mr. Zip as simplistic and “crude,” his whimsical nature helped gain public recognition.

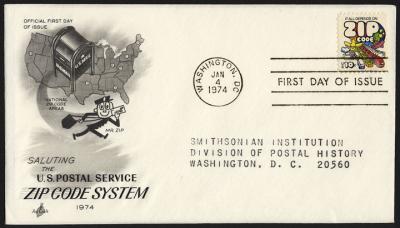

Mr. Zip and the zone improvement plan were unveiled at a postmasters convention in October 1962. The image soon appeared in post offices, on streetside mail boxes, in advertisements in collaboration with the Advertising Council and in story placements in national and local media to urge mailers to use ZIP code on mail. Every mailbox in the country received a ZIP-A-List Kit explaining the code and how to use it.

Even AT&T was involved. The telecommunications giant around the same time was introducing the use of area codes in phone numbers. The company shared its experience in educating customers about such a significant change of habit to aid postal officials in their introduction of a new way of doing things.

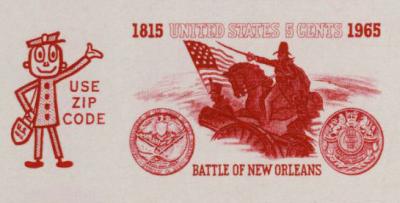

Mr. Zip never appeared on a stamp though. He was featured instead on the margin of stamp panes and stamp booklets with the message to “USE ZIP CODE.”

The marketing campaign continued throughout the 1960s. Only one stamp, a colorful 10-cent adhesive issued Jan. 4, 1974, ever promoted the use of ZIP code on mail.

Mr. Zip was retired in the 1980s.

As mail handling became more automated, post office thinkers began to consider ways to make mail delivery and sorting even more efficient. In 1983, the ZIP+4 system was introduced. It assigned four additional numbers to a code to identify the block or floor of a building for which mail was intended. Even so, much mail today bears just a five-digit code.

Even with the use of such technology, the U.S. Postal Service continues to struggle in some locales with delayed delivery or lost mail. Furthering USPS woes, mail volume has seen a steady, almost prolific, decline in the 21st century as electronic communication and online commerce has skyrocketed.

In fiscal year 2024, the USPS processed 112.5 billion pieces of mail, a significant decline from 213 billion pieces in 2006. More troubling for the Postal Service is the rapid drop in first-class mail. Peaking at 103.6 billion in 2001, first-class mail volume stood at 44.3 billion in 2024.

Conversely, the USPS has seen sizeable growth in package delivery, reaching 7.1 billion in 2023.

Dennis Sadowski can be reached at sadowski.dennis@gmail.com